The Letters And Poems Of Samuel Beckett 701am

This document was ed by and they confirmed that they have the permission to share it. If you are author or own the copyright of this book, please report to us by using this report form. Report l4457

Overview 6h3y3j

& View The Letters And Poems Of Samuel Beckett as PDF for free.

More details h6z72

- Words: 2,112

- Pages: 7

The Letters and Poems of Samuel Beckett By PAUL MULDOONDEC. 12, 2014 Photo

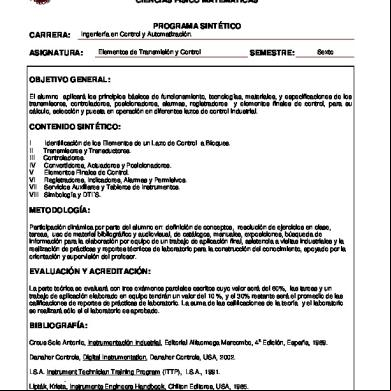

Samuel Beckett in West Berlin, where he directed "Endgame," September 1967. Credit Konrad Giehr/dpa Picture-Alliance, via Associated Press

In a 1964 response to an inquiry from his Hungarian publisher, Europa Konyvkiado, Samuel Beckett gives a handy thumbnail sketch not only of his career but of his character:

“As a writer I have no feeling of any national attachment. I am an Irishman (Irish port) living in for the past 27 years who has written part of his work in English and part in French. The following plays were written in French: ‘En attendant Godot’ ‘Fin de Partie’ ‘Actes Sans Paroles I & II’ and the following in English ‘Cascando’ ‘Krapp’s Last Tape’ ‘All That Fall’ ‘Embers’ ‘Words & Music’ ‘Happy Days’ ‘Play’ “If you should see fit to include one of the latter in your British anthology and one of the former in your French I should be pleased. If this is not possible and a choice must be made, I should prefer to figure in your French anthology.” While this isn’t quite so pithy as Beckett’s retort to a French journalist on the question of his being English (“Au contraire”), it does nonetheless give the gist of his contrarian, and often contradictory, personality. For much of Beckett’s work sets itself against something, be it turning up his nose at the selfdelighting verbal high jinks that he refers to as “the stink of Joyce,” or turning his back on the conventions of the narrative arc and dramatic action. The letters collected here come in the wake of the success, in 1955, of the English version of “Waiting for Godot,” the play in which, according to the critic Vivian Mercier, “nothing happens, twice.” One of the few things that do happen is that the tree that’s barren in Act I develops some foliage in Act II. But, as the high priest of lessness writes to the director Jerzy Kreczmar of the 1957 Warsaw production — “The tree is perfect (perhaps a few leaves too many in the second act!)” — even that mustn’t be overstated. The contradictory nature of Beckett is everywhere in evidence here. On one hand there’s the fastidiousness about the “leaves too many.” On the other is the fierce self-deprecation and disengagement, whereby “Watt” is “my regrettable novel,” " ‘Godot’ was written either between ‘Molloy’ and ‘Malone’ or between ‘Malone’ and ‘L’Innommable,’ I can’t ,” and, about his radio play “Embers,” “Hate the sight of it in both languages.”

This last occurs in a letter of Dec. 1, 1959, to Barbara Bray, the BBC drama producer who oversaw the 1958 version of “All That Fall,” Beckett’s first radio play. The editing of this third volume of “The Letters of Samuel Beckett” is no less exemplary than that with which we’ve come to be familiar from the first and second, but the entry on Bray in the “Profiles” section is a masterpiece of tact and tacitness: “Few people can have come so close to SB. Lively, inventive and with a strong literary sensibility, she was the ideal person to help him through his characteristic lack of confidence about the new medium — not least because she saw at once that it was perhaps, of all the media, the one best suited to his gifts. SB was soon to feel totally at home with the BBC Sound Drama team (the others at that time were Donald McWhinnie and John Morris), but his connection with Bray, while unfailingly and productively professional, went well beyond that.”

Why radio might be the medium “best suited” to Beckett comes down to a single concept — silence. No writer has understood the power of silence better than Beckett. No one has understood better than Beckett that silence is not an absence of sound but a physical presence, perhaps even a character. That certainly seems to be the case with “Krapp’s Last Tape,” the monologue he wrote for Patrick Magee, which is the single greatest evocation of loss and longing of the 20th century. (Beckett’s affection for Magee is one of the many heartwarming discoveries of this volume.) It’s no accident, so, that it was an icon of the “silent” era, Buster Keaton, who would star in Beckett’s “Film” (1965), shot in some of the more dilapidated areas of Lower Manhattan. The slapstick humor we associate with much of Beckett’s work is rarely to be seen in the letters. Knockabout gives way to nuance. For example, in 1959 he writes to Bray about his experience of reading “Doctor Zhivago,” a copy of which she had given him as a present: “I have finished Pasternak with mixed feelings, which is more than I hoped for.” In 1958, meanwhile, he’d written to Bray of the death of her estranged husband with what we come to recognize as his trademark tenderness: “All I could say, and much more, and much better, you will have said to yourself long ago. And I have so little light and wisdom in me, when it comes to such disaster, that I can see nothing for us but the old earth turning onward and time feasting on our suffering along with the rest. Somewhere at the heart of the gales of grief (and of love too, I’ve been told) already they have blown themselves out.” It’s the phrase “I’ve been told” that is the clincher here. It is wry in the face of wretchedness, sly in the face of the onslaught, and it rather cleverly hints to a recent victim of viduity that someone who might yet be capable of love may be waiting in the wings. I use the word “viduity” because Krapp uses it to describe his mother dying “after her long viduity.” One of the paradoxes we see again and again is that the Beckett who is so often inclined to cut everything back to the bone, to avoid the excess he associates with Joyce, is capable of the very linguistic derring-do he purports to hold in disdain. I think of him allowing

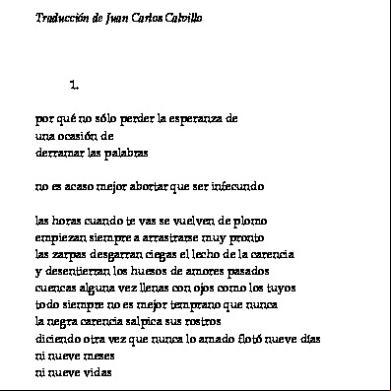

himself to pun on the phrase “Emerald Isle” with a very Joycean “Haemorrhaldia.” I think of him referring to the “rose grey nags” of his new Citroën 2CV (deux chevaux). Such wordplay is, of course, much more associated with Beckett’s poems, going right the way back to “Whoroscope,” written in 1930 for a competition run by the Hours Press and judged by Richard Aldington and Nancy Cunard. He writes to Cunard in 1959: “ ‘Whoroscope’ was indeed entered for your competition and the prize of I think 1,000 francs. I knew nothing about it till afternoon of last day of entry, wrote first half before dinner, had a guzzle of salad and Chambertin at the Cochon de Lait, went back to the Ecole and finished it about three in the morning. Then walked down to the Rue Guénégaud and put it in your box. That’s how it was and them were the days.” Whatever “Whoroscope” might smell of, it’s certainly not the lamp. Like so many of Beckett’s poems, and unlike any of his prose or drama, it has a half-done quality. The main problem is twofold. To begin with, Beckett has almost no sense of how a line functions in verse making. To describe his line breaks as arbitrary would be a kindness. The second, related difficulty is that he is fatally under the sway of his contemporaries in Irish modernism, notably Thomas MacGreevy, who seem to understand the idea of representing fracture but without the concomitant need for some sort of fusion and farrier-work. Opening “The Collected Poems of Samuel Beckett” at random, one comes upon this: My cherished chemist friend lured me aloofly down from the cornice into the basement drew bottles of acid and alkali out of his breast to a colourscale accompaniment (mad dumbells spare me!) fiddling deft and expert with the double ted nutcrackers of the hen’s ovaries

“Mad dumbells spare me” indeed! I think it’s fair to say that were Beckett’s name not hovering around in its vicinity, this poem would not be published by Grove Press or anyone else. The idea that this edition might include “previously unpublished” material begins to seem more of a threat than a promise! Beckett’s self-disparaging 1957 letter to Eva Hesse on her translation of his poems into German (“You have my heartfelt sympathy”) is not at all misplaced. Writing in 1957 to Grove Press’s Barney Rosset about the idea of publishing his poems, Beckett speaks better than he knows: “I have lost many and not all are worth reprinting. There is one wild love one called ‘Cascando’ you might like. An American bitch.” Leaving aside the tone of this last sentence, which is so out of tune in its boys-will-be-boys crudity with the rest of the letters, a quick read of “Cascando” will reveal the following: the churn of stale words in the heart again love love love thud of the old plunger pestling the unalterable whey of words Again, this is truly dreadful stuff. Why go to the effort of establishing the metaphorical system of churning butter and then appeal to the quite different system of “pestling”? It’s the kind of failure of nerve to which Beckett rarely succumbed in his other work. This “Cascando” of 1936 is not to be confused, for example, with the “Cascando” of 1964, the English version of a radio play originally written in French. Starring Denys Hawthorne and Patrick Magee and produced by Donald McWhinnie, “Cascando” was broadcast on Oct. 6. On or about that day, Beckett wrote to Peter Hall of the Royal Shakespeare Company that “a season of my work at the Aldwych would of course give me great pleasure.” By Oct. 20, 1964, the Beckett who was capable of such enthusiasm was just as capable of writing to Barney Rosset to ask for the presses to be stopped: “I have broken down halfway through galleys of ‘More Pricks Than Kicks.’ I simply can’t bear it. It was a ghastly mistake on my part to imagine, not having looked at it for a quarter of a century, that this old [expletive] was revivable. I’m terribly sorry, but I simply have to ask you to stop production.” This enduring, endearing self-doubt is a mark of most great writers. For some, it may seem like a pose. Not for Beckett. Again and again, this volume of letters allows Beckett to come off as being genuinely assured of his vision of, say, how a part should be interpreted (describing one recalcitrant actor as “another Beckett specialist”), while being genuinely uncertain about his own role. Writing to the translator Arland Ussher in 1962 sher’s musings on “Beckettism,” he asserts:

“My unique relation — and it a tenuous one — is the making relation. I am with it a little in the dark and fumbling of making, as long as that lasts, then no more. I have no light to throw on it myself and it seems a stranger in the light that others throw.” On Jan. 8, 1958, Beckett had complained to Rosset that the director Alan Schneider planned to draw on their correspondence for an article in The New York Times: “I am disturbed by the letter montage. . . . I dislike the ventilation of private documents. These throw no light on my work.” The following day, however, Beckett wrote to Schneider himself: “Your letter of Jan. 5 today. Shall answer it properly (?) tomorrow or this evening. This in haste to get something off my muckheap of a mind. I received from Barney yesterday jacket of book and extracts from our letters, with no indication of what the latter was for. This disturbed me as I do not like publication of letters. I wrote to him at once saying I shd prefer the letters not to be used unless it was important for you that they should be. I see from your letter that it is and this is simply to say all right, go ahead. . . . Thanks for the photos, they do me full justice.” One may be in no doubt that, even on a bad day, even on a day when all his ironies are to the fore, Beckett would have concluded that this magnificent project does him just that.

THE LETTERS OF SAMUEL BECKETT Volume III: 1957-1965 Edited by George Craig, Martha Dow Fehsenfeld, Dan Gunn and Lois More Overbeck Illustrated. 771 pp. Cambridge University Press. $50.

THE COLLECTED POEMS OF SAMUEL BECKETT A Critical Edition Edited by Sean Lawlor and John Pilling 499 pp. Grove Press. $35.

Samuel Beckett in West Berlin, where he directed "Endgame," September 1967. Credit Konrad Giehr/dpa Picture-Alliance, via Associated Press

In a 1964 response to an inquiry from his Hungarian publisher, Europa Konyvkiado, Samuel Beckett gives a handy thumbnail sketch not only of his career but of his character:

“As a writer I have no feeling of any national attachment. I am an Irishman (Irish port) living in for the past 27 years who has written part of his work in English and part in French. The following plays were written in French: ‘En attendant Godot’ ‘Fin de Partie’ ‘Actes Sans Paroles I & II’ and the following in English ‘Cascando’ ‘Krapp’s Last Tape’ ‘All That Fall’ ‘Embers’ ‘Words & Music’ ‘Happy Days’ ‘Play’ “If you should see fit to include one of the latter in your British anthology and one of the former in your French I should be pleased. If this is not possible and a choice must be made, I should prefer to figure in your French anthology.” While this isn’t quite so pithy as Beckett’s retort to a French journalist on the question of his being English (“Au contraire”), it does nonetheless give the gist of his contrarian, and often contradictory, personality. For much of Beckett’s work sets itself against something, be it turning up his nose at the selfdelighting verbal high jinks that he refers to as “the stink of Joyce,” or turning his back on the conventions of the narrative arc and dramatic action. The letters collected here come in the wake of the success, in 1955, of the English version of “Waiting for Godot,” the play in which, according to the critic Vivian Mercier, “nothing happens, twice.” One of the few things that do happen is that the tree that’s barren in Act I develops some foliage in Act II. But, as the high priest of lessness writes to the director Jerzy Kreczmar of the 1957 Warsaw production — “The tree is perfect (perhaps a few leaves too many in the second act!)” — even that mustn’t be overstated. The contradictory nature of Beckett is everywhere in evidence here. On one hand there’s the fastidiousness about the “leaves too many.” On the other is the fierce self-deprecation and disengagement, whereby “Watt” is “my regrettable novel,” " ‘Godot’ was written either between ‘Molloy’ and ‘Malone’ or between ‘Malone’ and ‘L’Innommable,’ I can’t ,” and, about his radio play “Embers,” “Hate the sight of it in both languages.”

This last occurs in a letter of Dec. 1, 1959, to Barbara Bray, the BBC drama producer who oversaw the 1958 version of “All That Fall,” Beckett’s first radio play. The editing of this third volume of “The Letters of Samuel Beckett” is no less exemplary than that with which we’ve come to be familiar from the first and second, but the entry on Bray in the “Profiles” section is a masterpiece of tact and tacitness: “Few people can have come so close to SB. Lively, inventive and with a strong literary sensibility, she was the ideal person to help him through his characteristic lack of confidence about the new medium — not least because she saw at once that it was perhaps, of all the media, the one best suited to his gifts. SB was soon to feel totally at home with the BBC Sound Drama team (the others at that time were Donald McWhinnie and John Morris), but his connection with Bray, while unfailingly and productively professional, went well beyond that.”

Why radio might be the medium “best suited” to Beckett comes down to a single concept — silence. No writer has understood the power of silence better than Beckett. No one has understood better than Beckett that silence is not an absence of sound but a physical presence, perhaps even a character. That certainly seems to be the case with “Krapp’s Last Tape,” the monologue he wrote for Patrick Magee, which is the single greatest evocation of loss and longing of the 20th century. (Beckett’s affection for Magee is one of the many heartwarming discoveries of this volume.) It’s no accident, so, that it was an icon of the “silent” era, Buster Keaton, who would star in Beckett’s “Film” (1965), shot in some of the more dilapidated areas of Lower Manhattan. The slapstick humor we associate with much of Beckett’s work is rarely to be seen in the letters. Knockabout gives way to nuance. For example, in 1959 he writes to Bray about his experience of reading “Doctor Zhivago,” a copy of which she had given him as a present: “I have finished Pasternak with mixed feelings, which is more than I hoped for.” In 1958, meanwhile, he’d written to Bray of the death of her estranged husband with what we come to recognize as his trademark tenderness: “All I could say, and much more, and much better, you will have said to yourself long ago. And I have so little light and wisdom in me, when it comes to such disaster, that I can see nothing for us but the old earth turning onward and time feasting on our suffering along with the rest. Somewhere at the heart of the gales of grief (and of love too, I’ve been told) already they have blown themselves out.” It’s the phrase “I’ve been told” that is the clincher here. It is wry in the face of wretchedness, sly in the face of the onslaught, and it rather cleverly hints to a recent victim of viduity that someone who might yet be capable of love may be waiting in the wings. I use the word “viduity” because Krapp uses it to describe his mother dying “after her long viduity.” One of the paradoxes we see again and again is that the Beckett who is so often inclined to cut everything back to the bone, to avoid the excess he associates with Joyce, is capable of the very linguistic derring-do he purports to hold in disdain. I think of him allowing

himself to pun on the phrase “Emerald Isle” with a very Joycean “Haemorrhaldia.” I think of him referring to the “rose grey nags” of his new Citroën 2CV (deux chevaux). Such wordplay is, of course, much more associated with Beckett’s poems, going right the way back to “Whoroscope,” written in 1930 for a competition run by the Hours Press and judged by Richard Aldington and Nancy Cunard. He writes to Cunard in 1959: “ ‘Whoroscope’ was indeed entered for your competition and the prize of I think 1,000 francs. I knew nothing about it till afternoon of last day of entry, wrote first half before dinner, had a guzzle of salad and Chambertin at the Cochon de Lait, went back to the Ecole and finished it about three in the morning. Then walked down to the Rue Guénégaud and put it in your box. That’s how it was and them were the days.” Whatever “Whoroscope” might smell of, it’s certainly not the lamp. Like so many of Beckett’s poems, and unlike any of his prose or drama, it has a half-done quality. The main problem is twofold. To begin with, Beckett has almost no sense of how a line functions in verse making. To describe his line breaks as arbitrary would be a kindness. The second, related difficulty is that he is fatally under the sway of his contemporaries in Irish modernism, notably Thomas MacGreevy, who seem to understand the idea of representing fracture but without the concomitant need for some sort of fusion and farrier-work. Opening “The Collected Poems of Samuel Beckett” at random, one comes upon this: My cherished chemist friend lured me aloofly down from the cornice into the basement drew bottles of acid and alkali out of his breast to a colourscale accompaniment (mad dumbells spare me!) fiddling deft and expert with the double ted nutcrackers of the hen’s ovaries

“Mad dumbells spare me” indeed! I think it’s fair to say that were Beckett’s name not hovering around in its vicinity, this poem would not be published by Grove Press or anyone else. The idea that this edition might include “previously unpublished” material begins to seem more of a threat than a promise! Beckett’s self-disparaging 1957 letter to Eva Hesse on her translation of his poems into German (“You have my heartfelt sympathy”) is not at all misplaced. Writing in 1957 to Grove Press’s Barney Rosset about the idea of publishing his poems, Beckett speaks better than he knows: “I have lost many and not all are worth reprinting. There is one wild love one called ‘Cascando’ you might like. An American bitch.” Leaving aside the tone of this last sentence, which is so out of tune in its boys-will-be-boys crudity with the rest of the letters, a quick read of “Cascando” will reveal the following: the churn of stale words in the heart again love love love thud of the old plunger pestling the unalterable whey of words Again, this is truly dreadful stuff. Why go to the effort of establishing the metaphorical system of churning butter and then appeal to the quite different system of “pestling”? It’s the kind of failure of nerve to which Beckett rarely succumbed in his other work. This “Cascando” of 1936 is not to be confused, for example, with the “Cascando” of 1964, the English version of a radio play originally written in French. Starring Denys Hawthorne and Patrick Magee and produced by Donald McWhinnie, “Cascando” was broadcast on Oct. 6. On or about that day, Beckett wrote to Peter Hall of the Royal Shakespeare Company that “a season of my work at the Aldwych would of course give me great pleasure.” By Oct. 20, 1964, the Beckett who was capable of such enthusiasm was just as capable of writing to Barney Rosset to ask for the presses to be stopped: “I have broken down halfway through galleys of ‘More Pricks Than Kicks.’ I simply can’t bear it. It was a ghastly mistake on my part to imagine, not having looked at it for a quarter of a century, that this old [expletive] was revivable. I’m terribly sorry, but I simply have to ask you to stop production.” This enduring, endearing self-doubt is a mark of most great writers. For some, it may seem like a pose. Not for Beckett. Again and again, this volume of letters allows Beckett to come off as being genuinely assured of his vision of, say, how a part should be interpreted (describing one recalcitrant actor as “another Beckett specialist”), while being genuinely uncertain about his own role. Writing to the translator Arland Ussher in 1962 sher’s musings on “Beckettism,” he asserts:

“My unique relation — and it a tenuous one — is the making relation. I am with it a little in the dark and fumbling of making, as long as that lasts, then no more. I have no light to throw on it myself and it seems a stranger in the light that others throw.” On Jan. 8, 1958, Beckett had complained to Rosset that the director Alan Schneider planned to draw on their correspondence for an article in The New York Times: “I am disturbed by the letter montage. . . . I dislike the ventilation of private documents. These throw no light on my work.” The following day, however, Beckett wrote to Schneider himself: “Your letter of Jan. 5 today. Shall answer it properly (?) tomorrow or this evening. This in haste to get something off my muckheap of a mind. I received from Barney yesterday jacket of book and extracts from our letters, with no indication of what the latter was for. This disturbed me as I do not like publication of letters. I wrote to him at once saying I shd prefer the letters not to be used unless it was important for you that they should be. I see from your letter that it is and this is simply to say all right, go ahead. . . . Thanks for the photos, they do me full justice.” One may be in no doubt that, even on a bad day, even on a day when all his ironies are to the fore, Beckett would have concluded that this magnificent project does him just that.

THE LETTERS OF SAMUEL BECKETT Volume III: 1957-1965 Edited by George Craig, Martha Dow Fehsenfeld, Dan Gunn and Lois More Overbeck Illustrated. 771 pp. Cambridge University Press. $50.

THE COLLECTED POEMS OF SAMUEL BECKETT A Critical Edition Edited by Sean Lawlor and John Pilling 499 pp. Grove Press. $35.